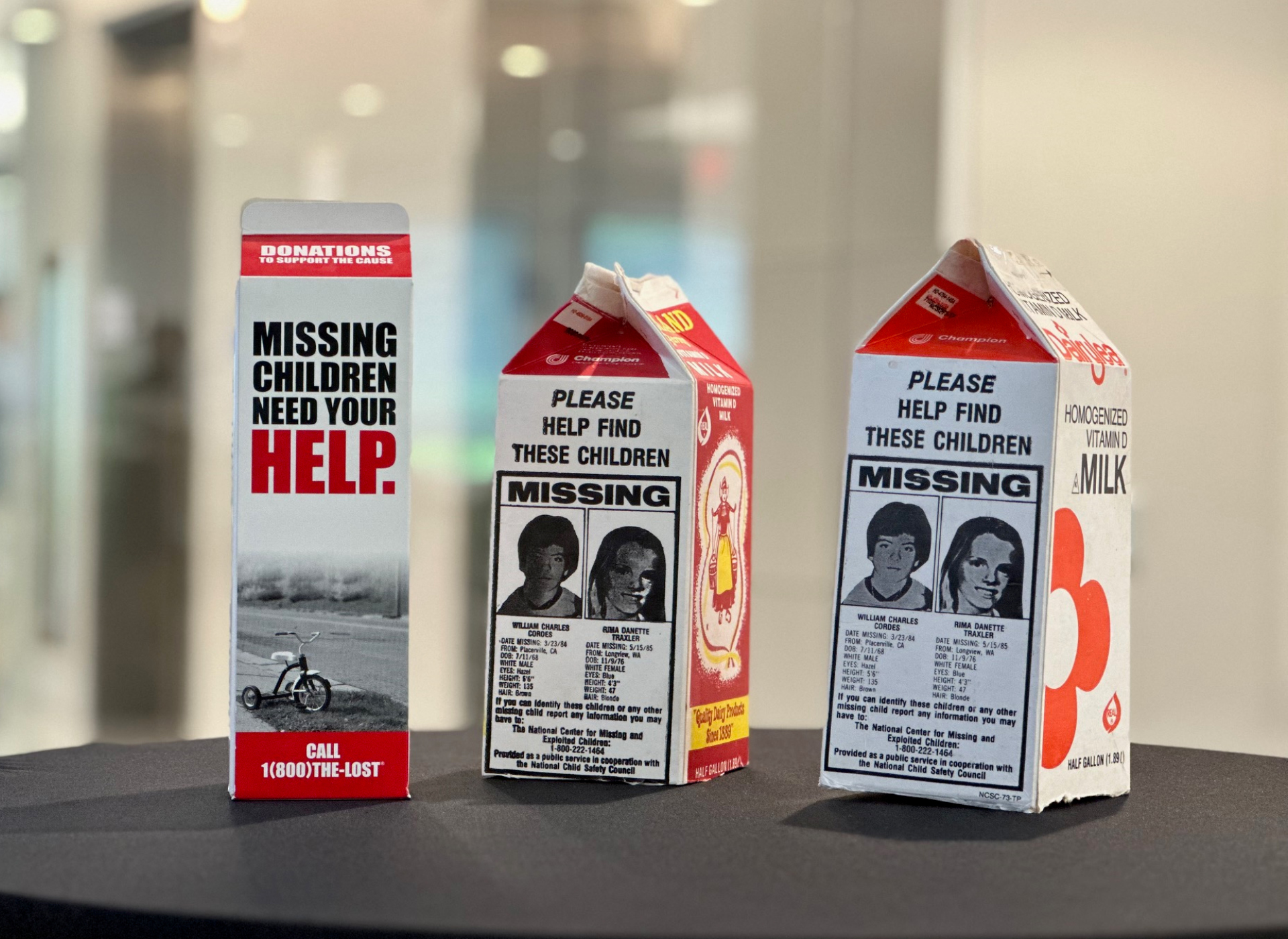

The Milk Carton Kids

Back in the mid-1980s – before the creation of the AMBER Alert system and much before a photo of a missing child popped up on your cellphone via social media – photos of missing children began circulating a different way, on an item nearly every family had on their breakfast table:

A milk carton.

Following a string of tragic events in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, the epidemic of missing children across the U.S. became increasingly apparent. Shocked and heartbroken from their own experiences, affected parents and a team of child advocates were prompted to take action. Their efforts sparked a powerful movement, which culminated in the creation of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in 1984.

With the public’s growing concern, many people and companies became eager to assist, looking for new ways that they could spread the word about missing kids.

And for a local dairy company in Iowa, that's exactly what they set out to do.

In September 1984, Anderson Erickson Dairy, local to Des Moines, Iowa, decided to use something they had right at their fingertips to push forward the mission. According to the Des Moines Register, the company decided to print two missing boys on the side of their milk cartons. For them, it was close to home, because the featured boys – Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin – were local. Both boys had been abducted on their paper route: Martin less than a month earlier in August 1984, and Gosch in 1982.

An Anderson Erickson Dairy Milk Carton. (Credit: Colorado Public Radio)

That original half-gallon milk carton seemed to inspire a movement. According to the Register, just a few weeks later, more dairy companies across Iowa began to participate. The program started to spread, hitting cities like Chicago and reaching as far as California. According to the National Child Safety Council, by December 1984, their nonprofit took interest and expanded the program by initiating the first nationally coordinated "Missing Children Milk Carton Program." Within weeks, the National Child Safety Council had partnered with more than 700 dairy manufacturers across the country, responsible for circulating cartons nearly everywhere.

And what was printed on the carton? A toll-free hotline number for a brand-new child protection organization: The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children at 1-800-843-5678.

Or rather, 1-800-THE-LOST.

Missing children on a milk carton. (Credit: NCMEC)

At the time milk cartons began circulating, NCMEC was an extremely new organization, driven by a team of advocates who came together to push forward a mission that aimed to make the world a safer place for children. Much like today, central to advancing that mission was the need for the public’s attention. To get the word out, NCMEC needed “poster partners,” which were other companies and groups that offered a widespread place where we could put out pictures of missing kids and reach a national audience to find them.

And that’s exactly what our participation in the milk carton campaign aimed to do.

Back then, NCMEC’s photo distribution team was much smaller than it is today. Before posters were sent out to partners at the click of a button, pictures – often grainy and not-so-great – were sent out via mail. The team spent their days packing brown paper mailers full of missing kid posters, stamping them and sending them around the country to be featured on all kinds of different products.

At the time, leadership at NCMEC was faced with numerous questions on how this would all work. Who would we send the pictures to? What information would we include? And how do we ensure that these pictures are getting into the right hands, on the right products and in front of the right people?

Behind every poster, there was serious thought: Where can we place this picture to give this kid the best shot at being found safely?

This still happens today.

With newly found contacts across the country, NCMEC was able to attempt geotargeting for the first time, selecting cases that were relevant to specific areas based on location. And it wasn’t just milk cartons. Around the same time, NCMEC was working with other partners, and posters were appearing on other items, grocery bags, buses and even right in people’s mailboxes.

The original ADVO mailer flier of missing Cherrie Mahan. (Credit: The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Gosch and Martin were soon joined by others who took on the title of the “Milk Carton Kids,” including Etan Patz. Patz disappeared from New York in 1979 while on his way to his bus stop. In 1983, President Reagan proclaimed his missing date of May 25 as National Missing Children’s Day to honor his memory.

Despite its widespread reach, the campaign wasn’t without its critiques. In fact, the idea was heavily criticized by some. Some felt like placing missing kids in front of other children at the breakfast table did nothing but scare children and push forward a “stranger danger” narrative.

Here at NCMEC, we know that “stranger” abductions are the rarest type of missing child case. In fact, fewer than 1% of cases reported to NCMEC are classified as nonfamily abductions.

Others felt that given the large number of missing child cases that were placed on the side of milk cartons, the recovery rate was low. Statistically, not that many children were found as a direct result of the program. However, there are some success stories, including a 7-year-old child in a family abduction case who recognized her face on the side of the carton and reunited with her father, and a teen from Lancaster who returned home after seeing the image.

1/2: Newspaper Article from October 1985. (Credit: Fort Walton Beach Playground Daily News); 2/2: Newspaper Article from January 1985. (Credit: Kannapolis Daily Independent)

By the late 1980s, the campaign began to fade out and was gone almost entirely by the invention of the AMBER Alert system in 1996. However, a few individual companies were still printing kids on milk cartons even in the late 1990s. Today, the image of a missing child on a milk carton is one that many Americans recall vividly, and despite the critics, the campaign did accomplish one major thing – it brought awareness to missing kids and opened a door to brand-new ways to get missing children in front of the public eye.

“The original milk carton campaign was really one of the first steps in mass distribution of missing child posters,” said John Bischoff, vice president of NCMEC’s Missing Children Division. “That campaign laid the foundation for what we are able to do today and made people start to think: How else can we get the public to pay attention and assist in the search for these missing kids?”

And today, that’s exactly what we do at NCMEC. Photographs of missing kids are at your breakfast table in a different way, at the power of your fingertips via cellphones, social media and even on the morning news.

The essence of the campaign – putting a face to the name and rallying community support – remains at the heart of efforts to locate missing children. Milk cartons are now billboards, grocery bags turned into GSTV pumps and even missing child posters are enhanced, featuring QR codes targeted to your area. Over the past 40 years, we’ve transformed with the times, yet we’ve stayed true to our mission, assisting in the recovery of more than 426,000 missing children.

Whether it’s a milk carton, a mall kiosk, a television screen or a Ring notification on your phone, we'll never stop searching until all missing children come home.

---

To view missing child posters in your area, visit www.missingkids.org/search.

To read more about NCMEC’s 40th anniversary, read our blog here: https://www.missingkids.org/blog/2024/40-years-of-hope.